© Renault

A MODEL’S PERPETUAL EVOLUTION

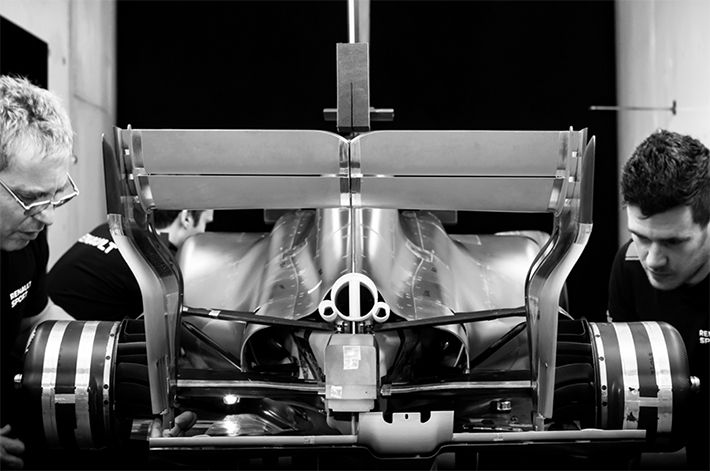

As the recipient of an aerodynamicist’s ideas, a scale model is in perpetual evolution, with elements or their alterations added with each passage through the wind tunnel thanks to a fluid process.

“On the model we have about 300 to 400 pressure taps – predominantly on the underside of the car – of 1 mm diameter,” specifies Simon Hines. “On the actual race car we have something similar, not really as many taps as we have here. They have annoying things like engine, gearbox and driver to fit in their car! (Laughs) We can just pack these things full of sensors.

“The core is full of sensors and made of a metal spine, but the entire surface is plastic. Most of the 600 parts weekly produced by the advanced digital manufacturing end up on the model.

“The external parts are stored for a while and then end in the bin. The internals (the spine and the sensors) are strip back, recalibrated, re-checked and re-built to be put be in operation again. We have two models in rotation, and we make sure the spine remain constant.

© Renault. Old models were mainly made of aluminium.

“The model should be a few weeks ahead of the race car. We don’t necessarily react immediately to a race result, because we should be ahead of it, but there are instances where if some pressure data suggests that something is not behaving we may come back and do some specific test just to try to understand what it might be.

“The percentage of the parts tested that go on the race car is not as high as we would like. CFD is not yet perfect. We have big rotating tyres, we have the proximity with the ground. It is a far more complicated model than let’s say designing a civil aircraft.”